This is the story of G.C. who has courageously shared his deeply personal journey of foreskin restoration, reclaiming his body and autonomy, and overcoming years of shame. His path is one of healing, empowerment, and self-discovery.

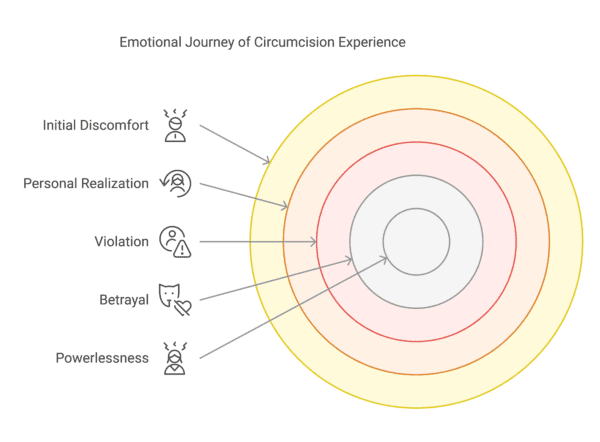

I was only five or six when I first realized something wasn’t right. I stood there in the bathroom, staring at myself in the mirror, and then looking at the other boys around me while I was in Europe. They seemed… different. They were intact. I wasn’t. I didn’t know what it meant at the time, or how to put it into words, but something deep inside me felt off.

There was a knot of confusion in my chest, a sense of betrayal, like I was somehow incomplete. I didn’t understand it then, but I could feel it—an unspoken difference that would linger in my mind for years.

Anger, confusion, and resentment were quietly planted in the corners of my heart, roots growing deeper with each passing year, unanswered and unresolved.

The Early Years: A Sense of Loss Without Explanation

For most of my childhood, I didn’t question it. It was like a low hum in the background of my life—a quiet, nagging discomfort I couldn’t name or place. I couldn’t explain it, and maybe, I didn’t even try. There was this sense of unease that lingered, an invisible weight that tugged at me without reason or understanding.

For most of my childhood, I didn’t question it. It was like a low hum in the background of my life—a quiet, nagging discomfort I couldn’t name or place. I couldn’t explain it, and maybe, I didn’t even try. There was this sense of unease that lingered, an invisible weight that tugged at me without reason or understanding.

But as I got older, and the world around me started making more sense, that quiet discomfort turned into something much more tangible. I began to understand what circumcision was—not just the sterile, clinical definition, but what it truly meant. It wasn’t some routine procedure. It wasn’t just a part of life, a simple tradition. No, it was a forced, irreversible alteration of my body—a genital modification performed on me without my consent. And suddenly, it hit me like a cold slap in the face: this wasn’t something abstract. It was real. It was personal.

I felt like my body had been stolen from me. It wasn’t just a procedure. It wasn’t just a decision made in the name of tradition or religion. It was a violation—one I had no control over, no voice in. Someone else had made a choice for me, and now I had to live with the consequences. Every time I thought about it, it felt like a robbery, like something fundamental was taken from me without my permission.

And as time went on, that sense of betrayal grew. I felt so small, so powerless. The people who were supposed to protect me, to make decisions in my best interest, had instead chosen to make a decision that would affect me for the rest of my life—without asking, without consulting, without even trying to understand how I might feel about it. I wasn’t given a say. I wasn’t given a choice.

And worst of all, I felt powerless, trapped in a past that I couldn’t change, haunted by a decision I didn’t make.

The Decision to Restore: A Private Act of Defiance

I first discovered foreskin restoration in my early teens. The idea of reclaiming something so personal, something taken from me without my consent, deeply fascinated me. But I kept my research a secret, ashamed and embarrassed. Society doesn’t acknowledge the pain of circumcised men, and I wasn’t sure how anyone would react if they found out I wanted to “undo” what had been done.

At first, it seemed impossible. The thought of stretching what little skin I had left to mimic the natural covering of an intact man felt like wishful thinking. But as I read more, hearing the stories of others who had done it, my doubt slowly turned into cautious optimism.

It wasn’t just about the body—it was a quiet act of defiance, a way to reclaim a part of myself that had been stolen. Every step forward felt like I wasn’t just restoring my body, but taking back my identity.

The Early Struggles: Shame, Frustration, and the Fight Against Hopelessness

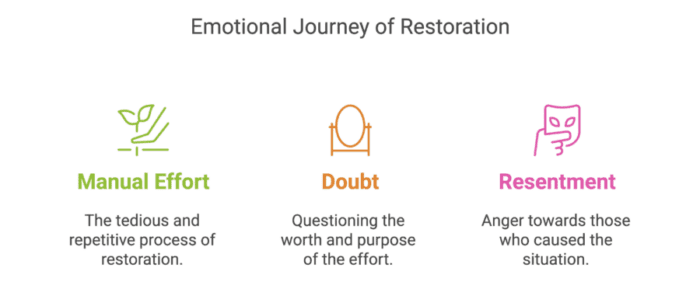

Restoration is a slow, grueling process, one that tests your patience, your willpower, and your sanity. In the beginning, I resorted to manual tugging techniques—small, deliberate movements each morning meant to coax the skin into expanding. It was tedious, almost cruel in its repetitiveness. Every day felt like a reminder of how far I had to go. For months, I saw no real progress. The weight of hopelessness pressed down on me like a suffocating blanket.

Restoration is a slow, grueling process, one that tests your patience, your willpower, and your sanity. In the beginning, I resorted to manual tugging techniques—small, deliberate movements each morning meant to coax the skin into expanding. It was tedious, almost cruel in its repetitiveness. Every day felt like a reminder of how far I had to go. For months, I saw no real progress. The weight of hopelessness pressed down on me like a suffocating blanket.

There were days when I could hardly bring myself to keep going. I’d find myself staring at my reflection, questioning everything. Why am I doing this? Is this even worth it? Am I just wasting my time and energy? The doubt was relentless, an insidious whisper that would not let me be. And then came the shame—the toxic, suffocating kind that whispered I was ridiculous for even trying, for thinking that I could undo what had been done to me.

But there was more. Beneath it all simmered a deep, unspoken resentment—toward my parents, who made a decision about my body without so much as asking for my input, toward the doctors who performed the procedure with no real understanding of its long-term consequences, and toward a society that brushed it off as nothing, as if it wasn’t a big deal. It was a big deal. It had shaped my body, altered my sense of self, stolen away my pleasure, and, in many ways, warped my identity. Every moment of this journey felt like a battle—not just against the physical limitations of my body, but against the emotional scars that had been left behind.

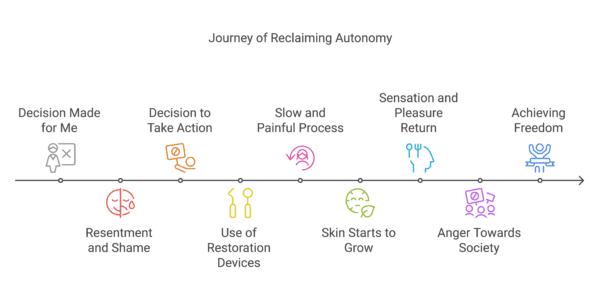

The Emotional Rollercoaster of Restoration, The Progress and Renewed Motivation

It wasn’t until my mid-20s that I finally took control of my body. For years, I had lived with the consequences of a decision made for me—by someone else, at a time when I couldn’t even comprehend its full weight. A decision that altered my body, my identity, without my consent. But somewhere along the way, something inside me snapped. I could no longer live with the quiet resentment and shame. I couldn’t ignore the deep-rooted feeling that something crucial had been taken from me—something I had every right to reclaim.

It wasn’t until my mid-20s that I finally took control of my body. For years, I had lived with the consequences of a decision made for me—by someone else, at a time when I couldn’t even comprehend its full weight. A decision that altered my body, my identity, without my consent. But somewhere along the way, something inside me snapped. I could no longer live with the quiet resentment and shame. I couldn’t ignore the deep-rooted feeling that something crucial had been taken from me—something I had every right to reclaim.

So, I decided to take action. I committed to using restoration devices, stretching tools, and integrating them into my routine like a new form of training, a regimen to rebuild what had been lost. The process was slow, painful at times, but I was relentless. It wasn’t just about the physical recovery; it was about taking back my autonomy. And bit by bit, something incredible began to happen.

The skin started to grow.

At first, the change was barely noticeable—imperceptible, even. But as time passed, the transformation became undeniable. Each small sign of growth was a victory. For the first time in my life, I felt more whole, more intact. It wasn’t about how I looked in the mirror anymore. It was about how I felt. For the first time, I started to reconnect with my own body, to feel more like me—like the version of myself I was supposed to be all along.

The real transformation, though, wasn’t just physical. As my skin expanded, the glans—once exposed, vulnerable, and dull—began to shed the thick, calloused layer of keratin that had developed as a defense against the trauma. The return of sensation, something I had never fully understood before, was nothing short of a revelation. Real pleasure, something I had been denied, flooded back. It was like waking up after years of numbness.

But with that awakening came something fierce and painful: anger. Anger at my parents for making that choice for me without my voice in the matter. Anger at the doctors who never questioned it—who saw it as routine, as nothing more than a simple procedure, an inconsequential choice. And most of all, anger at society, which treated this violation of my body as if it were no big deal. But it was a big deal. It had shaped me in ways I could never have fully realized at the time. It had shaped my confidence, my self-worth, my very identity. Now, with each inch of growth, I was finally taking back what was mine—reclaiming the body and life I should have had from the start.

This wasn’t just about looking different. This was about becoming different. Taking control, finding strength, and making peace with myself. And with that came a sense of freedom—freedom I didn’t know I was missing until I had it.

The Turning Point: Taking Back My Power

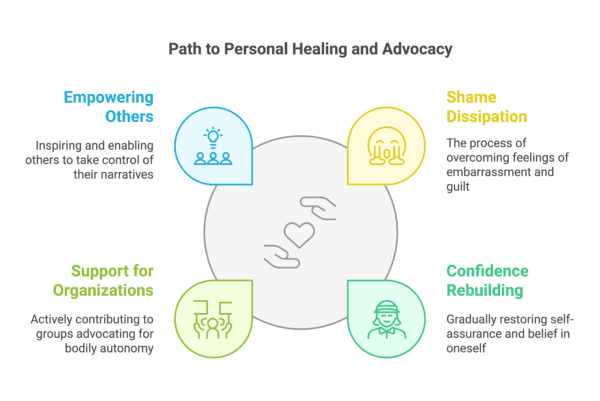

But here’s the raw truth: as I kept restoring, something inside of me started to shift. The weight of those feelings that once dominated me—fear, shame, helplessness—began to lose their grip. The more I took control of my own body, the more I realized just how much power had been stripped from me. And with each small step toward healing, the less of a victim I felt. I wasn’t just mourning the trauma anymore—I was actively fighting to reclaim every part of myself that had been taken.

It wasn’t a quick or easy process, but there came a moment—like a bolt of electricity—that I knew I had reached my turning point. I wasn’t just going through the motions; I was breaking free. I had stopped asking for permission to heal. I wasn’t waiting for someone else’s approval. I was taking what was rightfully mine. Every stretch, every effort, every little millimeter of skin I could regain—it all became a powerful act of defiance. I was no longer just a circumcised man—I was a man who had found his power again, one piece at a time.

That’s when it hit me: this wasn’t just physical restoration. It was emotional and spiritual too. I had transformed my pain into something unstoppable—purpose. And that purpose was bigger than anything I had ever known. I wasn’t just reclaiming my body—I was reclaiming my life, my autonomy, and my voice. Every step forward became a reminder: I was no longer powerless. I was a force in the making.

Unexpected Perks and Newfound Confidence

When I started looking intact, something inside me shifted in ways I didn’t expect. The shame, which had haunted me for years, began to dissipate. My confidence, once fractured, slowly started to rebuild itself piece by piece. That ugly, unnatural scar—constantly reminding me of what was taken—was no longer there to mock me. I looked at myself in the mirror and saw someone whole, someone at peace with their body in a way I never thought possible.

And with that peace came something even more powerful: a fierce drive to help others. It wasn’t just about me anymore. I realized I wasn’t alone in this—there were countless men out there fighting their own battles with the same scars, the same struggles, the same journey to healing. That realization set me on a new path.

I threw myself into supporting organizations like Intact America and Your Whole Baby—groups on the frontlines, fighting to end routine infant circumcision. It wasn’t just about raising awareness; it was about empowering others with knowledge, advocating for their right to bodily autonomy, and using my experience to stand up for those who didn’t yet have the courage to speak out. Every time I donated or shared my story, I felt a surge of purpose—a sense of belonging to something far bigger than myself.

The Importance of Community and Support

One thing I quickly learned on this journey: most therapists just don’t get it. The trauma of circumcision is real, but few are willing to acknowledge it. Finding support? That was a battle in itself. It was like I had to navigate a maze, searching for someone who truly understood what I was going through. But then I found something truly invaluable—community. Connecting with other men who had walked this painful road was like a balm to a soul that had been bleeding for years.

Hearing their stories—stories that mirrored my own—brought me a sense of validation I had been starving for. It made me realize I wasn’t the only one feeling the weight of what had been taken. It was a revelation that fueled my resolve. It wasn’t just about restoring my body anymore; it was about restoring my dignity, my voice, and my sense of self. And when things got tough—and believe me, they did—it was their strength that kept me going.

Final Thoughts: A Hard-Won Victory

Foreskin restoration isn’t easy. It’s a long, slow, and sometimes painful process. There are moments when it feels like you’re pushing against a wall that will never move. It can be emotionally exhausting, and there are times you’ll wonder if it’s worth it. But let me tell you this: it is. Every tear, every struggle, every setback—it’s all part of a journey that’s so deeply worth it.

If you’re considering foreskin restoration, let this be your reminder: you’re not crazy. You’re not alone in this. And you have every right to reclaim what was stolen from you. This journey is not just about regaining what was physically lost; it’s about healing, finding peace in your own skin, and ultimately taking back control of your body, your narrative, and your life.

This journey—this fight—has been one of the most transformative, powerful things I’ve ever done for myself. It’s a hard-won victory, but it’s a victory nonetheless. So, to anyone who’s struggling on this path: keep going. The road may be long, but the freedom you’ll find on the other side will make every step worth it.

No Comments